Reading ‘The Plague’ in the times of Coronavirus

"Ah, if only it had been an earthquake! A good bad shock, and there you are! You count the dead and living, and that's an end of it. But this here damned disease, even them who haven't got it can't think of anything else.”

(The Plague, page 56)

For last 3 months, every morning I google a number of coronavirus cases in India and worldwide. This number, which looks awfully similar to a video game score, is the indicator of our new normal. It tells me where we are today. This, for me and a lot of us, is the face of the pandemic. But a number on our screens can’t possibly show us the reality of loss and suffering. So, we go looking for more. Following this number is a bombardment of news reports about our fight against the virus – keeping up the morale, attempts at finding a cure, prevention measures, saluting doctors and frontline workers or so called COVID warriors. Words like fight, hero, warrior along with a score like number make the whole thing sound more and more like a video game, and a sense of absurdity sets in. Is this what a pandemic looks like? In these times of chronic uncertainty, our healthcare system has reached a breaking point, our economy is collapsing and the vulnerable sections of the society are the ones really bearing the brunt of it. We know this. It’s not that we don’t recognize the severity of situation. Yet, we struggle to understand the scale and implications of it. Things like pandemic, war, revolution are too big and too abstract to be real. It is challenging to make sense of abstract things. That is why in times like these we turn to works of literature and philosophy, works like Albert Camus’ ‘The Plague’. Because, it is especially challenging to make sense of abstract things when they are happening to you.

“Yes, an element of abstraction, of a divorce from reality, entered into such calamities. Still when abstraction sets to killing you, you've got to get busy with it.” (The Plague, page 43)

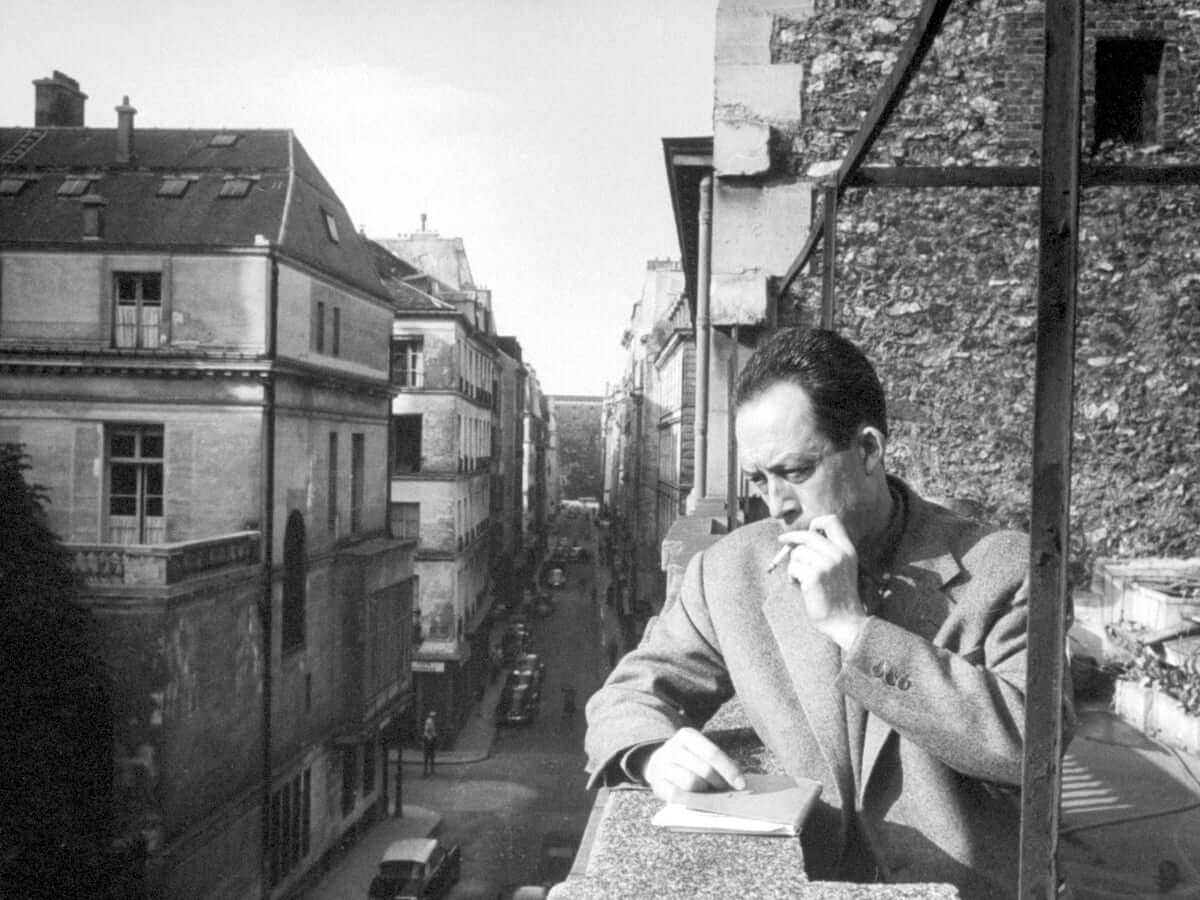

‘The Plague’ or ‘Le Pest’ by Albert Camus – first published in 1947 – has become a global sensation and is being hailed as a ‘guide to survive a pandemic’. While it may not be a guide, The Plague does provide a strange comfort. It talks about the town of Oran where people face a bubonic plague, and are quarantined for over a year. Focusing on a few characters, the book recounts every painful detail of the pestilence with a cold, scary objectivity. Some parts of the book actually read like a report, making the whole story feel uncomfortably real.

Initially, when a number of dead rats ominously start showing up in street corners, nobody pays much attention to it. Then, slowly, people start getting sick. Not enough to raise concern, just enough to cause worry to our main narrator, Dr. Rieux. As the sickness, with symptoms of Bubonic Plague, begins to spread and people start dying, the authorities take note. However, they are initially hesitant to declare it a plague as doing so would change things dramatically. When the number of sick get too large to ignore, they announce that the town is facing an outbreak of the plague. The town of Oran is locked down and new restrictions are implemented. Still, the town people see this more as a minor inconvenience that will go away in a few weeks. Restaurants and theatres remain open. People see this as an opportunity to rest. They make up new routines around new restrictions. The plague is still a distant unreal entity, not something happening to them. But, as weeks go by and the number of dead keeps steadily rising, the unease increases. Same show keeps playing in the theatre over and over again for months until the day a performer collapses on stage and dies. People get tired of visiting same cafes and restaurants. They start wandering around the town aimlessly. Quarantine centres are built for the sick. Those who were separated from their family members, lovers and friends begin to feel pangs of isolation and try to reach each other through all means possible. But during a time like this money, political connections and power means nothing. Everyone is suffering. The poor suffer the most as the prices of food and essential items skyrocket. With this slow suffering, a sense of melancholy spreads across the town. After a few months of sickness, people feel robbed of hope and future. They finally resign to the fact that this is real and is happening to them collectively. Religion gains a strong foothold as a source of comfort. With administrative and bureaucratic system overexerted, many volunteer to become part of sanitation groups to help out. Doctors and experts work tirelessly at a cure. In the end, the plague leaves the same way it had arrived, miraculously.

All this sounds quite relatable, doesn’t it? This is the awkward comfort of ‘The Plague’. This book tells us that this has happened before, that there is a pattern to it, and that it ends. Through different characters, we get to see different ways in which people react to the epidemic. The real value of this book lies in the fascinating variety of these reactions, which we will briefly look at.

I would like to start with a remote character that usually doesn’t get much attention. But I believe it is uniquely applicable to our time. In the beginning of the book, even before the plague has reached the town, a man named Cottard unsuccessfully attempts to commit suicide. Reasons for this action are left largely unspecified. This is a character facing extreme stress and psychological trauma in his daily life. What we see is that when the plague breaks out and the town is locked up, Cottard’s mood improves considerably. He likes this state of affairs where everyone else is suffering just as he was.

“…fear seems to him more bearable under these conditions than it was when he had to bear its burden alone” (The Plague, page 96)

Now that mental health has become the buzzword, it is important to realise that a stressed and exhausted mind finds strange ways to cope with something as severe as a pandemic. It is equally important to understand such coping mechanisms and find your own ways to deal with them. When the plague subsides and the town is opened again, Cottard is unable to handle it.

When the plague is rising, religion suddenly take precedence. The general outlook underlying this is ‘what harm could it do?’ The epidemic is seen as a test by believers which helps boost the morale. However, it only lasts for some time. As the disease keeps getting stronger - developing different strains and outsmarting all attempts at a cure - people begin to lose faith in religion. Witnessing suffering on this scale is bound to cast doubt on anyone’s faith. Character of father Paneloux tries to defend his faith by believing the plague to be a divine punishment. He preaches that people getting the plague have done something wrong and therefore deserve the plague. This act of defence stems from the philosophy of Catholic religion, as the story takes place in French Algeria. In India, we have strong notions of purity and impurity in our religious ideologies. So, we get to see patients discriminated against by many individuals and groups for being infected or impure. Religious dogmatism has a tendency to creep up in different places in different forms. The book does a wonderful job of describing some of them.

Tarrou is another interesting character. A keen observer and a lonesome individual, he is our second narrator. He initiates and leads the voluntary sanitation groups. His reasoning for stepping up to work at frontline is something very personal – curiosity. He wants to know if it is possible to become a saint without believing in God. Similar story of Rambert- a travelling journalist, who is stuck in Oran as the town is locked up. He is severely affected by the separation from his lover. Throughout the first half of the book he keeps trying to leave the town by any means possible. Finally, when he gets a rare chance to escape the town and go home, he decides to stay back to help out our protagonists. He believes finding personal happiness at the backdrop of communal misery to be distasteful. There is a beautiful piece of conversation around this -

“Doctor," Rambert said, "I'm not going. I want to stay with you."

Tarrou made no movement; he went on driving. Rieux seemed unable to shake off his fatigue.

"And what about her?" His voice was hardly audible.

Rambert said he'd thought it over very carefully, and his views hadn't changed, but if he went away, he would feel ashamed of himself, and that would embarrass his relations with the woman he loved.

Showing more animation, Rieux told him that was sheer nonsense; there was nothing shameful in preferring happiness. "Certainly," Rambert replied. "But it may be shameful to be happy by oneself."

(The Plague, page 101)

There is a pattern to the disease and people’s reactions to it. Reasons may vary, but actions are the same. People work together, to minimise the casualties of the pestilence.

Our main narrator Doctor Rieux is the first to recognize the plague and suggest preventive measures. When the plague spreads, he oversees the healthcare system of the town and works tirelessly to treat the patients. It is believed that Albert Camus, a proponent of absurdist and existentialist philosophy, wrote the character of Dr. Rieux after himself. Therefore, Rieux’s point of view is a combination of these philosophies. They suggest that life is inherently absurd, that there is an underlying disharmony in the relationship between our existence and the world. There is no grand reason or explanation why things like pestilence or natural calamities occur. This makes suffering inevitable in life as we, human beings, crave meaningfulness and order. But Camus tells us to embrace the absurd and live life in whatever capacity we can. We must create our own meaning to survive. Thus, we see that Dr. Rieux, facing a losing battle, tries to save as many people as he can. He suffers grave personal losses. Still he keeps on working tirelessly to help other suffering individuals. Because, according to him, that is the only thing he really can do in face of an epidemic. One may be tempted to call him a hero. Anticipating this, Camus offers us a critique of heroism in the first half of the book:

“…by attributing overimportance to praiseworthy actions one may, by implication, be paying indirect but potent homage to the worse side of human nature. For this attitude implies that such actions shine out as rare exceptions, while callousness and apathy are the general rule. The narrator does not share that view. The evil that is in the world always comes of ignorance, and good intentions may do as much harm as malevolence, if they lack understanding.” (The Plague, page 65)

This critique is something we should endorse. Heroism and idealism are the unsustainable ideologies we tend to rely on during difficult times. This reliance, however, does more harm than good. Idealising few individuals tend to absolve other members of society of their responsibility. Our goal should not be to be exceptional or heroic, but to be decent and kind towards each other collectively. We are not looking for heroism in the times like these. Heroes are few. Times like these needs everybody’s participation. What we need right now is kind people, good neighbours and responsible citizens.

“That's an idea which may make some people smile, but the only means of righting a plague is, common decency.” (The Plague, page 81)

Saee Pawar

psaee.888@gmail.com