Reclaiming Roots, Resisting Marginalisation: The Second Mahila Kisan Sammelan: A Documentation of a Decade’s Journey and Emerging Possibilities

At a time when mainstream agrarian discourse continues to marginalise the very hands that sow our sustenance, the 2nd National Mahila Kisan Sammelan stands as a powerful testament to feminist resistance rooted in soil, struggle and solidarity. What unfolded in Pune was not just a conference; it was a collective assertion of identity, where women farmers from across India came together to claim their space as cultivators, knowledge-keepers and decision-makers. In our agri-development society, when a male farmer dies by suicide, it is often the woman who is left behind to bear the burden alone. She grieves the loss while carrying the weight of unpaid loans, land disputes, and household survival, all without being recognised as a farmer. This harsh reality is at the heart of why MAKAAM’s ten-year journey is so important, and why spaces like the Sammelan are necessary. From seed exhibitions and testimonies of structural violence to the birth of the National Mahila Kisan Manch, the Sammelan brought together voices that have long been ignored. These voices don’t just demand inclusion; they are shaping a new vision of Indian agriculture, one grounded in care, equality and collective leadership. This is not a side story to the farmers' movement. This is the movement itself.

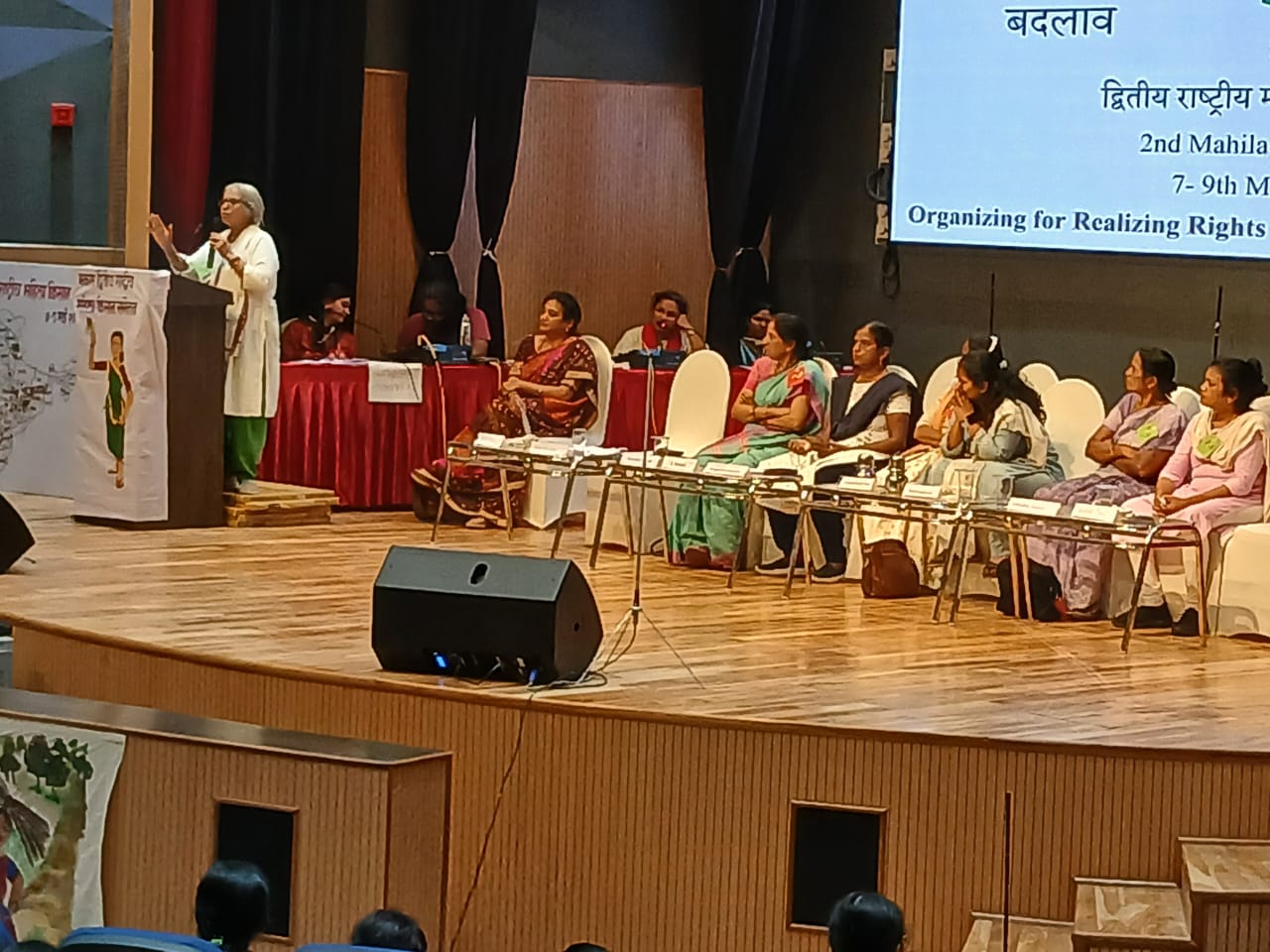

"Hum bharat ki naari hain, phool nahi chingari hain, (We are the women of India — not delicate flowers, but sparks of fire!)" declared one speaker at the 2nd National Mahila Kisan Sammelan, held from 7th to 9th May 2025 at Savitribai Phule Pune University. Organised by Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch (MAKAAM) in collaboration with the Department of Women and Gender Studies, the Sammelan marked a decade of MAKAAM’s transformative journey toward recognising women as farmers, rights-holders, and leaders.

More than 500 participants from 17 states across India came together for this vibrant, multilingual and multi-generational gathering.

A lot of prior preparation went into the making of the Sammelan. There were several initial meetings wherein the themes for each plenary session were discussed and argued for in great detail. Each plenary session was anchored by two or three members of the NFT.

For many of the parallel sessions, experts from the larger network affiliated with MAKAAM were invited to design and anchor the sessions such as Dr. Nitya Ghotge from ANTHRA, Dr. Alice Morris and Neeta Hardikar from the WGWLO/SWAL network from Gujarat, and Dr. Divya Veluguri from Deccan Development Society and Dr. Niranjana Maru.

All plenary and parallel session anchors put together discussion notes that were shared with the women farmers.

The resources for the bearing the cost of the Sammelan were raised partly through the registration fees, partly through an online fundraiser and mainly through the generous contributions of a couple of member organisations. Local organisations and individuals also pitched in for travel expenses to ensure that women farmers from their state or region would be able to attend the Sammelan in large numbers.

Celebrating a Decade of Feminist Agrarian Assertion

The gathering opened on a deeply resonant note, with the inaugural plenary framing both the mood and the message of the Sammelan. Dr. Swati Dehadroy of Savitribai Phule Pune University welcomed participants by affirming the need to bridge academic discourse with grassroots wisdom.

Seema Kulkarni of MAKAAM reflected on the platform’s decade-long journey—one that had built bridges between advocacy, research, and on-ground mobilising to assert women’s identity as farmers. Ulka Mahajan, a human rights activist and member of the Bharat Jodo Yatra, dismantled the myth of divine femininity, asking how a society that worships women as goddesses can continue to deny them land, rights, and recognition. “हम बेचारी नहीं हैं” (We are not helpless), she declared, capturing the spirit of defiance that ran through the Sammelan.

Dr. Navsharan Singh, associated with the farmers’ movement, issued a political warning about how state actors co-opt feminist language to defuse radical demands: “आपकी मांगें भुला दी जाएंगी और एक नया माहौल, एक नया संदर्भ आपके ऊपर लाद दिया जाएगा” (Your demands will be forgotten, and a new narrative will be imposed on you). From Assam, Moon Bora laid bare the stark wage gaps that women face, especially in informal rural economies. Kumari Bai Jamkatan described how displacement and forest enclosures strip Adivasi women of not just land but identity, and how few even have their names on forest titles.

Dr. Aruna Roy joined via Zoom, urging the Sammelan to draw strength from collective organising—reminding everyone that while women’s labour may be fragmented, their solidarity is transformative.

Plenaries That Moved, Stirred, and Strategised

Following the opening plenary, four thematic plenaries were held—each structured to surface regional voices, sharpen collective demands, and articulate a feminist vision for transformation.

The first thematic plenary - Organising for Realising Rights of Women Farmers, explored how collective organising is essential to transform entrenched inequalities and assert rights. Sejal Dand opened by declaring, “There is no alternative to organising.” Sejal and co-facilitator Vaishali Patil framed the session around grassroots struggles where women not only raised their voices but also secured land, work, and dignity. Jashodhara Vanjara shared how joining Panam Mahila Sangathan enabled her to demand land rights and confront domestic violence. Shanthi Gangadharan highlighted how Dalit women in Tamil Nadu built cooperative organic farming initiatives to challenge caste and gender hierarchies.

Dr. Kavita Ware, a sarpanch from Maharashtra, laid out a practical roadmap for local governance, advocating stamp duty waivers and women's inclusion in land titling and welfare schemes. Ningamma Savanur of Karnataka described grassroots campaigns among Dalit women that exposed the limits of state delivery. Velvizhi from Tamil Nadu’s Fish for All Centre emphasised how fisherwomen remain invisible in policy despite anchoring the marine economy. Sunita Kashyap from Uttarakhand’s Umang Producer Company spoke of building a 25,000-woman enterprise and called for rural market infrastructure and support for women-led FPOs. Concluding the session, Nisha Shivurkar reminded participants that women farmers’ struggles must confront not only economic injustice but also rising authoritarianism and majoritarian power.

The second thematic plenary session on Structural Violence laid bare how systemic forces shape women’s lives in agriculture, from landlessness and poverty to exclusion from legal protections. Seema Kulkarni opened the session by critiquing the gender blindness of state policies and institutions. Geetha Ramakrishnan spoke of long-standing struggles to create welfare boards for unorganised workers and demanded sector-specific legal protections. Manisha Tokle highlighted how sugarcane-cutting girls from tribal communities face hazardous work and early marriage, while receiving less than minimum wage and no facilities.

Manjulata recounted how Adivasi families in Chhattisgarh were violently evicted by power projects, with women beaten and displaced. Mudapu Yadamma from Telangana described her journey from abuse to land ownership and leadership. Sukhwinder Kaur spoke of Punjab’s deep gender crisis—from female foeticide to systemic denial of land to widows. Chhaya Kharkhate narrated the resistance faced by women leaders asserting transparency in local governance. Meera Sanghamitra concluded by urging the Sammelan to frame violence not as episodic, but as rooted in patriarchy, capitalism, and state neglect that systematically exclude women from land, decision-making, and justice.

The third thematic plenary session on Forest Rights and Commons, spotlighted the struggle of women forest-dwellers and pastoralists who continue to be excluded from decision-making despite their central role in stewarding commons. Radha Chand from Uttarakhand recounted how access to firewood and fodder is shrinking, with tragic consequences like fatal animal attacks. She spoke of mobilising women to demand recognition and compensation. Mansi Asher of Himdhara Collective critiqued how global climate finance programs instrumentalise women’s labour while sidelining them from governance. She warned against greenwashing gender equity.

Veena Baria from Gujarat described how forest officials falsify plantation records to block women’s FRA claims. Navlibai Garasia from Rajasthan spoke of schemes that sidestep Gram Sabha consent, and Munni Hansda from Jharkhand called for full implementation of PESA and FRA. Rabari Suraj Bijalbhai shared how pastoralist women in Gujarat regenerate commons through collective governance and local rules. Across voices, women demanded not symbolic inclusion but structural control over resources, funds, and decisions affecting their forests and futures.

The fourth thematic plenary session on Feminist Agroecology explored the future of food sovereignty through a gendered lens. Rooted in lived practices, it challenged extractivist agriculture and emphasised seed sovereignty, ecological stewardship, and collective cultivation. The plenary echoed the call to broaden the definition of 'farmer' to include not only landowners but also cultivators, sharecroppers, pastoralists, and fisherfolk.

Speakers like Nafisa Barot framed feminist agroecology as a political practice—one that reclaims autonomy over seeds, markets, and decisions. Shalini Mahadevappa from Karnataka questioned why women who grow crops are denied the right to set their prices. Meena Kumari from Andhra Pradesh spoke about collective seed-saving and millet restoration, while Vimla Rathore from Rajasthan asserted that traditional knowledge passed down through generations is no less valuable than academic degrees. Lata from Chhattisgarh reminded the gathering that true agroecology connects crops with water, forests, animals, and soil.

The plenary emphasised that agroecology is not just about methods, but about power—who controls resources, whose knowledge is recognised, and who makes decisions about food and land. It urged state and institutional recognition of women’s practices and leadership in ecological farming systems.

Parallel Sessions: Grounded, Specific, and Unflinchingly Honest

Spread across two days, the ten parallel sessions brought together women from varied geographies and sectors, each bringing sharp insights from their contexts. In the session on farm suicides, women spoke not just of grief but of bureaucratic battles over compensation and dignity. Young rural women voiced how caste and gender combine to block access to education and opportunity. In another room, Dalit and Adivasi women agricultural workers shared stories of unsafe migration, wage theft, and invisibility in schemes meant to protect them.

Women from the coastal and livestock economies demanded recognition as producers, not helpers. In the land rights session, participants called for collective title deeds and access to the commons. The session on forest rights echoed this demand, with women resisting dispossession in the name of conservation. Across discussions on agroecology and seed sovereignty, women outlined strategies rooted in local knowledge, mutual aid, and community control.

Rather than isolated demands, what emerged was a dense fabric of shared struggle and feminist vision—a demand to redesign the agrarian system itself, not just seek inclusion in its margins.

Creative Resistance: Theatre and Collective Memory

The cultural evening on the first day featured a powerful performance of the play “Vhay, Mi Savitribai”, enacted in Hindi by actors Shilpa Sane and Shubhangi Bhujbal. Through monologues and shifting roles, the play traced Savitribai Phule’s journey—from her childhood and marriage to Jyotiba, to her transformation into an educator and reformer.

The performance also depicted key figures like Fatima Shaikh, Sagunabai, and Dnyanoba Sasane, highlighting the collective spirit of social reform. The portrayal of the Phules’ fight for the rights of Dalits, women, and widows resonated deeply with the audience, many of whom saw echoes of their own struggles. The play set the tone for the Sammelan’s feminist ethos—linking past resistance with present organizing.

The second evening of the Sammelan came alive with songs and dances performed by women farmers themselves, many of them Adivasi women dressed in their traditional attire. Delegations from Odisha, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka, and Telangana shared their cultural expressions—singing in their own languages, performing circle dances, and filling the air with drumbeats and joy.

The songs spoke of land, forests, resistance, and collective memory. The women brought not only rhythm and movement, but the weight of histories carried in their voices.

The Seed Exhibition was a vibrant space where over 20 groups of women farmers from 10 states displayed a rich diversity of desi seed varieties—millets, pulses, rice, vegetables, and medicinal herbs—alongside value-added products like pickles, flours, herbal powders, and snacks. Organised as part of the “Seeding Futures” initiative, the exhibition reflected the ecological and cultural knowledge of women farmers and collectives.

The Pune Declaration: Not Just Words, But a Political Roadmap

The Sammelan culminated in the adoption of the Pune Declaration, a collective articulation of vision and demands. The Pune Declaration was drafted in the backdrop of growing national resistance to extractive policies and with echoes of Pahalgam’s strong call for peace and justice. A strong anti-war sentiment resonated across the Sammelan, as women condemned violence not only in their homes and fields but also in the name of statecraft and conflict. Participants voiced an unequivocal refusal of war and militarism, demanding investments in care, food sovereignty, and ecological restoration instead.

The Declaration drew directly from testimonies drawn from the plenary and parallel sessions. It reflected the urgent need to reimagine power—away from corporate control, and toward feminist, community-led futures.

Here is a quick recap of the major demands from the declaration:

Legal recognition of women as farmers Structural redressal of systemic violence faced by women in agriculture, including gender-based violence, caste-based exclusion, and institutional neglect Recognition and protection of the forest rights of Adivasi and forest-dwelling women Reservations in all land allocations Gender-disaggregated data in all government schemes Full implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2008 and PESA Support for single women, widows, and women in farm suicide households Community-based mental health services Cultivator registries that reflect actual tillers, not just landowners Barriers against corporate land acquisition Expansion of women-led agroecological initiatives Recognition of forest-dwelling and pastoralist women as primary right-holders Toward Collective Leadership: The Formation of the National Mahila Kisan Manch

One of the most significant outcomes of the Sammelan was the formation of the National Mahila Kisan Manch—a collective forum envisioned to strengthen the leadership of women farmers across the country. This wasn’t a symbolic gesture; it was the outcome of deep, state-level deliberations that took place throughout the Sammelan.

Each state group met to reflect on their regional challenges, articulate priorities, and select women farmer representatives who would carry these concerns into a national agenda. The discussions were democratic and grassroots-led, allowing farmers themselves—not just organisational facilitators—to set the terms of representation.

This process culminated in a plenary where each state presented its action plan and introduced its selected leaders. The mood was electric—this was not just about who speaks for whom, but about who sets the agenda. Women from tribal, coastal, and drought-prone regions came forward to claim leadership roles.

The formation of the Mahila Kisan Manch represents a historic shift. It affirms that women farmers must not only be recognized as cultivators—but as political actors, agenda-setters, and movement-builders.

As the Sammelan drew to a close, one could sense a shift—not just in language but in imagination. From forest peripheries to fisher harbours, sugarcane fields to seed banks, women are not waiting to be included. They are leading.

MAKAAM’s work over the last decade shows that feminist agrarian politics is not an add-on to farmers' movements—it is central to any meaningful transformation. The 2nd National Mahila Kisan Sammelan was not a culmination but a continuation. A reminder that the future of agriculture in India will be written not in boardrooms, but in the fields and by the women who till them.

As one banner at the Sammelan read: "Zameen, Jungle, Aurat: Sabka Adhikaar Hai." (Land, Forest, Woman: All have rights.) This is not just a slogan. It is a revolution in motion.