When they make films : Part 1

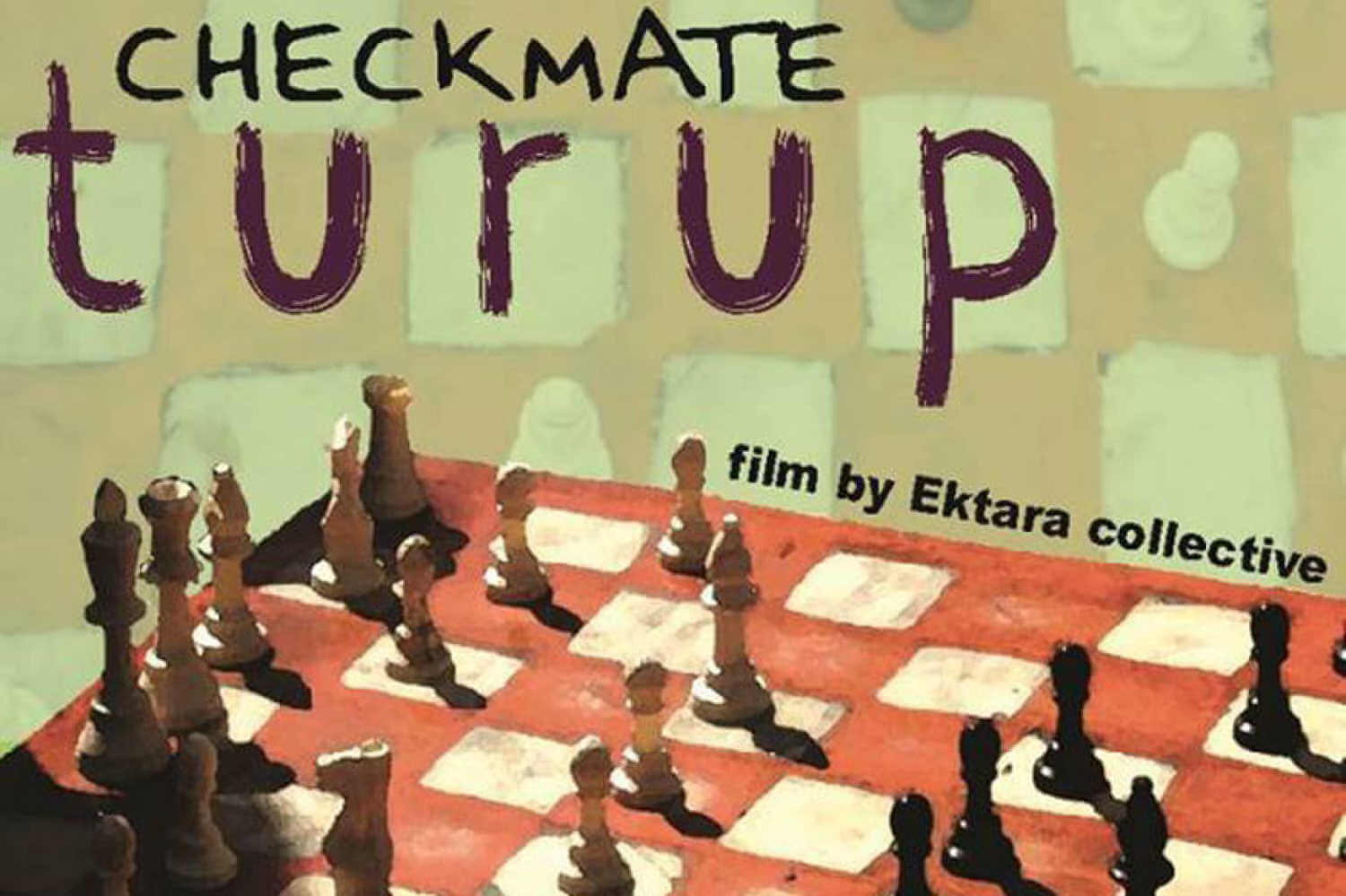

In this two-part series, social activist Shabana Diler interviews Maheen and Rinchin – two independent filmmakers who have paved a different, challenging and exceedingly interesting path for themselves. Through a collective effort, their fascinating journey has led them to make ‘Turup’ and ‘Agar wo desh banati’ – two remarkable films of our times. This part discusses making of ‘Turup’. Next one will be about ‘Agar wo desh banati’.

Turup Trailer from Ektara Collective on Vimeo.

When I saw the films, 'Turup' (तुरूप) and 'Agar Wo Desh Banati', (अगर वो देश बनाती) I was amazed by the magnificent photography of the films, its layout, its handling of topics and the content. I was keen to hear about the journey of the filmmaking from my two dear friends, Maheen and Rinchin (who had been instrumental in the making of these two films). In fact, I have known them for many years. We studied together at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences(TISS), where after post graduating in social work, the two joined the movement and worked extensively in the states of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, mainly with the laborers and women. While doing so, Rinchin also wrote some books, especially for children, most of which have been published by the Eklavya Publishing House. In the meantime, they also produced some short films through their group called Ektara Collective. While this was going on, Maheen completed a special course on Digital and Electronic Cinematography at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) to acquire the necessary skills for professional film making.

Each of their films is an idea, a process in which the audience - the actors - and everyone else travels in the same boat. We are impressed but we do not lose our capacity to think, in fact our thought processes become all the more dynamic while watching their films. Both these films, that portray a seemingly simple storyline, actually bring a whole new world of experience to the audience. Some people and activists from the local area have performed roles in the film that are very close to their own lives and therefore the roles that they perform are like their lived realities. These films tell stories about ordinary people, especially women, and about their wisdom. When women take charge of any struggle, it becomes more humane and inclusive, encompassing the entire ecosystem leading to victory. When Maheen and Rinchin take paper and camera in their hands, one can experience their feminist perspective and a tradition of historical struggle. One can see that they do not utter a single word about it, and yet we see its reflection throughout the story on the screen. And thus, we become fellow travelers in this journey.

In the movie Turup, they have used the game of chess quite effectively and symbolically to highlight different human relationships, politics and in general the current situation. It shows the love story of Majid (car driver) and Lata (cleaning worker). On the other side is Neelima, a journalist who is seeking medical treatment for conceiving a child. Moving ahead, she goes to do a press story of an incident through which we come to experience love and the communal politics surrounding it. Simultaneously, while there is a chess tournament going on in the local community, we get to know Monica, who works as a domestic help at Neelima’s house. She does not take part in the actual game of chess (being a woman), but she pays close attention to the game being played and the communal politics surrounding the same. It is an inspiring film that shows how the wisdom and conscience of ordinary people like Monika, Lata and others can rule over and help overcome the present situation. Crowd funded and crowd directed, Turup provides a whole new cinematic experience to the viewers.

======================================================================================================================================================================

In conversation with Maheen and Rinchin –

What is the meaning of Turup?

Turup means the trump card/turup ka patta.

How did you find the theme for Turup or what inspired you to make Turup?

It came from our lives. Chess is played in the locality that some of us live in. This has appeared in the film in much the same way, becoming a metaphor with a multifarious character. The other thematic of the film takes from what is happening around us - the rising force of Hindutva, the fanning of communal violence and the caste class discrimination that exists in our society. It is as we all experience it in our lives as people of a marginal identity in general and as women in particular. Thus, each character got in their lived reality, specially the women.

I understand that your production house is a collective of many people. Can you tell us a little more about your team and how you guys have come together?

Well, we all get our toes stepped on, elbowed, nudged etc. But there are also moments of perfect harmony and synchrony. Making films, especially independent films is a challenge and often people find it overwhelming to deal with the creative and ‘executing with limited resources’ aspects of it. Further, making independent cinema is seen as the path to finally making big production, big budget commercial films. Making independent cinema and working collectively to do it are core values of Ektara. It is an end in itself and those who have come together have a sense of this. The participation and ownership are also seen in this manner. This of course brings in its own set of challenges and there is little precedent to refer to or take validation from. As fellow travelers in a less explored territory, there is a lot of support that people give each other. If someone is faltering or an idea is not going through or even in just pushing and completing the work, many hands are extended to buoy the person/s and process, collective thinking is employed to grind idea blocks and many shoulders heave to push and complete difficult tasks and the film itself.

We are a group of individuals from different backgrounds with somewhat similar politics or point of view coming together to creatively and artistically express our drives. It is great to be working together. Of course, we all fight, we have differences, but we also have a collective vision and working collectively is also one of the ends along with what we create.

How do you manage to get such actors in your films?

I think their connection with the script allows them to give strong performance. Some of them are genuinely good actors who may or may not have acted before and for some playing a character close to their life also helps. Also, we do workshops. Some friends who are actors themselves from theater or films have helped in the workshops and rehearsals before the filming. The actors too help each other a lot on and between takes and rehearsals.

How do you derive your script? Is it written by a single person or does it get developed as you work on the project?

We all have different skill sets. But all of us have experiences/ideas/conversations to share. Those who can write take on the primary responsibility of being the scribes of these while weaving them into a dramatic, cinematic form; constructing the characters that play out this narrative. So, the contribution to the script is broad based but usually the main scripting is done by a smaller team of two or three people with discussion and brainstorming with a lot of people. There is a lot of back and forth and the script goes through many iterations. Also, the script is not treated as a static entity. It lives, grows and transforms as it makes its way to shooting. The actors, the camera, the sound, the edit and finally the audience breathe life into it.

For instance, the part where Maulina tells her mistress, “Shaadi hua nahi.. nahi; shadi kiya nahi!” or when she says “Pariwar to banane se banta hai.” These are lovely lines also spoken very well by your actor. Do elaborate how do you arrive at these lovely statements that leave an impact on the viewers.

Those were scripted. Some of them were in the original script. Some get innovated and tweaked while characters are rehearsing and responding to each other and even during the shoot itself. The two lines you mentioned came from what we feel as women and also from our lives where we are experiencing and creating families that do not always come from birth and marriage. It also is a lived experience for many of us. Shadi Nahi hui is a question that so many of us, especially women are asked, as if it’s a misfortune and Monika’s answer is an assertion of her choice.

Would you like to talk about the different processes/your experiences of the making of the film?

Casting is one of the most fun parts of making films. Many volunteer and many we approach. Some love acting and many do it because they believe in the story.

The film touches upon multiple issues of social concern and yet it’s not boring because these are not forced in as issues. They follow the characters, the story and the location. So, I guess that is why it seems to fit in with each other like a weave.

Domestic labour in the household is always shown in strange and insulting way and always from the point of view of the house owner since most films are about them. They are often shown as either just minions or often even as people who steal etc. Even when shown in a positive light they are there to support. The character of Monika was played by Maulini didi who herself is a domestic worker and she bought her own dignity to the screen and into the film. Many times, her wisdom and strength also contribute to the film making process on set. Even in real life many of us feel and have experienced life like that. Many of the members of the cast and crew are from working class and that’s why the perspective is different.

Lived experiences, many conversations and much reflection consolidate themselves into interactions like the ones you’ve mentioned on screen. We are a mixed group of gender, caste, religion and sexualities and here we find a safe space to bring in our lives in an uncensored sort of way. They mingle with each other, influencing the film, its making and us as people resulting in a refinement of our own understanding of each other’s lives and ultimately how we undertake the creative enterprise. There are points of convergence and points of divergence and they stay. We don’t try to force these into a neat resolution because often there isn’t one and we leave it to the audience to jostle with it just like we are doing. Many conversations are left open ended. So, in some senses the audiences also become fellow travelers undertaking this personal and political journey like and with us. And, if we are open enough, like the film itself we all too keep learning, changing, evolving through these encounters and a consistent engagement with them.

You have also managed to weave multiple stories into the main story that revolves around the game of chess.

That process was a very organic one. The connections emerged as lives of different characters crossed each other. The chess served as the perfect metaphor for the complexity of situations and what they threw up at the characters. We made a conscious choice to not force the story in any particular direction but to let it naturally unfold and reveal the layers embedded in it. The main thread of the story was enriched not just by what was said or seen or heard but also by what was left unsaid. The women in the film are never seen as a visible part of the chess games at the chauraha, but somehow their absence never takes away their influence or the essential role they play in life around the chauraha and its games.

The film also has some beautiful music and lovely lyrics. Can you talk about how you made this music happen?

The film demanded a certain kind of music. It had to be a natural extension of the subtlety and gentleness with which the most volatile challenges of our times are expressed in the film. Our films are often a departure from the classical way in which films are made. We always knew that there would be music in the film but it was only during the edit that it was tangibly conceptualized. Qawwali as a form was an obvious choice given that the story belongs to Bhopal and who better than Kabir to describe and address our times? The music was worked out by the musicians and singers from Dewas (a district close to Bhopal) in the Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh. A classical singer from Allahabad, Sangeeta Shrivastava became a part of the music team bringing in additional favour to the music. Several women from Bhiselkhedi village (where we recorded the music) who are self-taught also sang and recorded with us. For the film itself we had 3 songs but there is much more that we recorded with the women. This was one of the most enriching experiences for us.

How long did you take to make the entire film right from conceptualization till finish?

It took us about two years from start to finish. It may have taken less time but since all the labour of the cast and crew of the film was a contribution, people made time for it between their other daily wage work and job commitments.

How do you raise the funds for the making the film? And what is the budget of your film? (If you want to share it)

All the collaborators worked on a voluntary basis without any monetary remuneration. In the process where it is important to relate and interact with each other as equal, there is no question of having some people in the group paid and others not. The financial requirements for the shoot and the post production were met by raising money through individual contributions. Ektara does not take any kind of institutional funding. Institutional funding with externally imposed agenda driven controls is contradictory to a creative process where control has to come from within the group and not outside of it. There is no lower limit for making a financial contribution but yes, there is an upper limit. As a rule, no individual can contribute more than five thousand rupees to any film of Ektara collective. This ensures that more people know and become a part of the process and the ownership becomes extensive, broad based and collective. We spent around 3 lakh rupees on the film.

Lots of people who had seen ektara’s previous work and also who believed in the work contributed. Contributions came not just in the form of money but also time, skills, equipment, innovative ideas, technical workarounds, encouragement and several other things.

We’d like to mention here that there is a common notion that only work that is paid for is valued and if it cannot be paid for then you cannot demand quality from it. This notion does not hold true in cases where people value work itself as against monetary value of the work. In fact, in such cases it would be undermining to consider its worth merely in terms of money. We have seen this in every project that we have undertaken. The time and the effort to see them through may be more but in none of them has the quality of production been compromised. When people work collectively, they give their best and expect the same from their counterparts. This also comes from a culture where people are used to working and contributing physical and skill based labour. They are able to both appreciate and respect work and skills of others not as a commodity or a service but also as a means of expression.

Do tell us about the awards and the feedback you have received for Turup.

The feedback and the response have been overwhelming both from our audiences, festival audiences and critics. The film has had several screenings. It’s been shown in bastis, at informal/formal gatherings, in colleges and universities and at small and large festivals. We’ve realized that people are carrying and living with the film. As they watch it, they own it. What more could anyone ask for? Every audience has added a dimension to the film, giving it as much if not more than taking from it. People have written back on email, on their individual blogs and Facebook and of course have interacted in person wherever we could be present.

The take away from the film has been diverse. But one of the most touching comments was – ‘For a few minutes I thought that the ending was not true to reality. Then I understood what was meant to be conveyed was that the wisdom and humanity of the common people will triumph.’

This for us sums up the film in totality.

Festivals where the film was screened include –

- 19th Jio MAMI, Mumbai Film Festival, Mumbai, 2017

- 6th Dharamshala International Film Festival, Dharamshala, 2017

- Kazhcha Indie Film Fest, Kerala, 2017

- 11th Dialogues: Calcutta International LGBT Film and Video Festival, Kolkatta, 2017

- 3rd Raipur International Film Festival, Raipur, 2017

- Cinemas of Resistance Azamgarh, Udaipur, Patna, 2017-18

- 5th Kolkatta People’s Film Festival, 2018

- 41st Goteborg Film Festival, Sweden, 2018

- 14th IAWRT Asian Women’s Film Festival, 2018

- Chalti Tasveerein, Traveling film festival, 2018

- 9th The Bangalore Queer Film Festival, Bangalore, 2018

- 3d Indie Meme Film Festival, Austin, Texas, 2018

- 10th Hidden Gems Film Festival, Calgary, Canada, 2018

- 3rd Kashmir World Film Festival, Srinagar, 2018

- 3rd Mustard Seed Film Festival, Philadelphia, 2018

- 8th Chicago South Asian Film Festival, Chicago, 2018

- 1st Singapore South Asian International Film Festival, 2018

- 1st Pondicherry International Film Festival, 2018

Shabana Diler

shabanadiler1@gmail.com